Nagaland’s low NCRB crime figures mask widespread gender-based violence, underreporting, and systemic social silence revealed by frontline workers.

Share

DIMAPUR — As someone who has spent more than a decade responding to cases of gender-based violence across Nagaland, Lanuienla Imchen finds herself confronting an unsettling possibility: “Maybe Nagaland has never been the safest state for women in India in the first place.”

Her remark stands in contrast to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) 2023 data, which once again placed Nagaland at the bottom of India’s crime-against-women index—a statistical distinction often translated into the label “safest state.”

But on the ground, the numbers tell a different story.

According to Imchen, the Women Helpline 181 has received 2,07,987 calls since inception in 2016, of which only 3,408 were registered as formal cases.

More than 537 were classified as critical, ranging from severe domestic violence to threats to life. The rest, she said, never made it past the threshold of reporting as most women were held back by fear, stigma, or “for the sake of the children.”

“Crime has become an intrinsic part of Naga society,” she observed, adding that women have begun to internalise violence and accepted it as being part of life as a woman.

At the state’s One Stop Centres, 1,703 cases have been registered, almost all listed as critical, and 213 cases relate specifically to cybercrime.

Also read: Nagaland records 677 crime cases in first half of 2025

Cybercrime in Nagaland: INR 15 crore scammed in 18 months; INR 2 crore liened

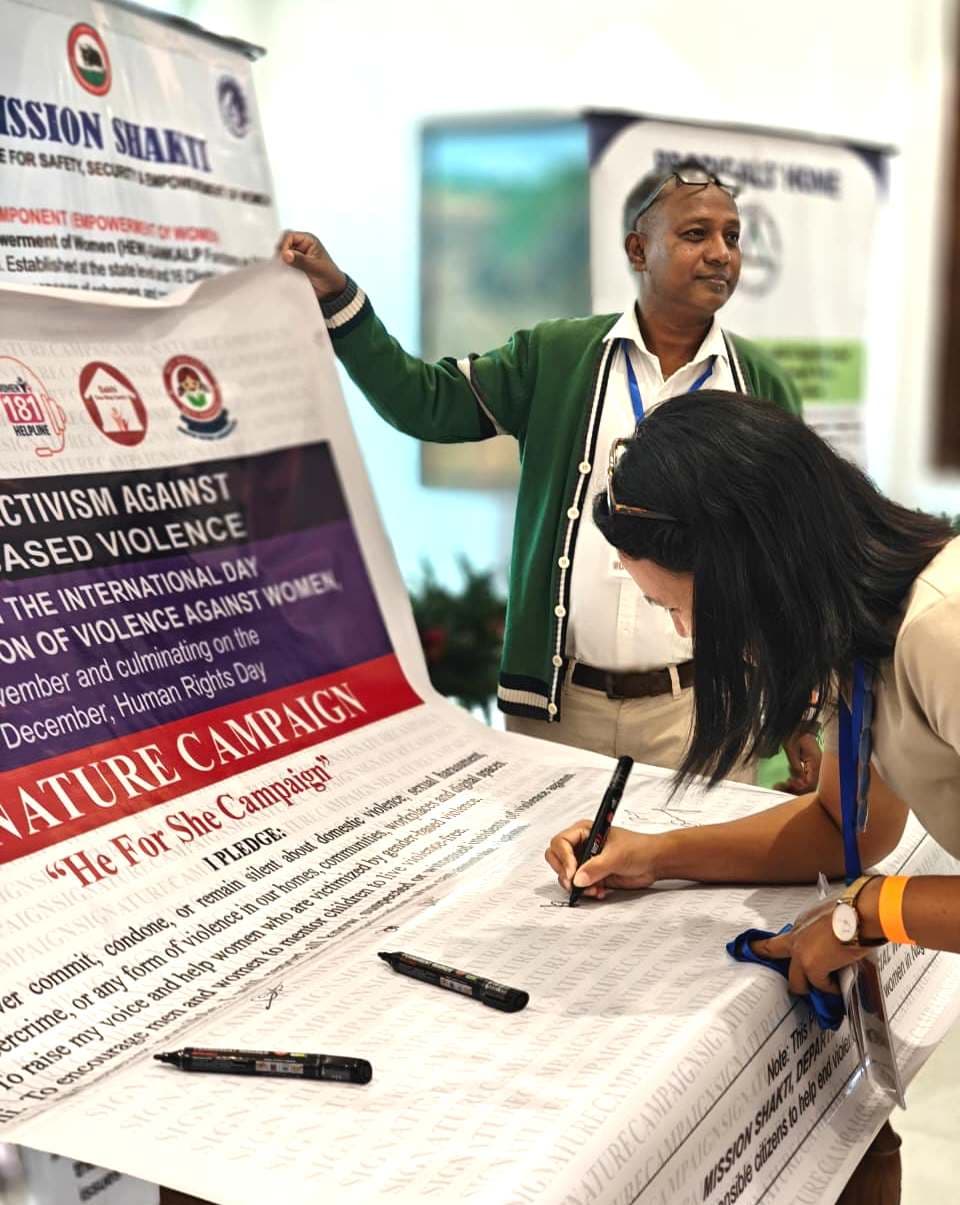

These concerns echoed across a room at Niathu Resort in Chümoukedima, where multiple stakeholders gathered under the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence on November 29.

WATCH MORE:

‘Compromise culture’

Neingu Kulnu, Administrator of Child Helpline 1098, presented another alarming set of numbers: over 13,400 calls since 2023 and 2,336 registered cases in total, out of which 1,212 were registered between April 2024 and November 2025.

In her experience, women often hesitate to seek formal help, but an equally painful truth, she said, lies within the community itself.

“When it comes to victimising the victims over and over again, we do not have to wait for men — we women do it ourselves,” she said, recalling several intervention cases where mothers, neighbours, or female relatives discouraged women from reporting violence in order to “avoid shame.”

From the Dimapur Police Commissionerate, DCP (Crime) & PRO Khekali Y Sema highlighted a pattern observed in Women Police Stations across the state: only 11% of domestic violence complaints become registered cases. The remaining 89% are “compromised.”

This culture of compromise, she said, forces women back into the very environment that harmed them, with no mechanisms to ensure safety afterward. She added that of the runaway and missing cases they handled, 90–95% involved women or children fleeing abusive or unhealthy environments.

So what does safety actually mean in such a context? And how long can Nagaland continue to rely on low reporting as a marker of safety?

‘The unwelcome truth’

Addressing these questions head-on was Dr. Villo Naleo, Secretary of the NBCC’s Social Concern Department, who acknowledged that churches—institutions expected to be “refuges for victims”—have at times become perpetrators through silence, reluctance, or fear of “taking sides.”

He also noted that some church leaders themselves have committed crimes against women.

Naleo urged the Church to abandon the culture of excusing violence through misinterpretations of forgiveness. “Forgiveness,” he said, “does not mean the legal punishment is cancelled.”

He called for “creative resistance,” arguing that humility is not passive suffering but taking a stand with dignity as an equal.

W Nginyeih Konyak, Chairperson of Nagaland State Commission for Women, reminded the gathering that even women themselves, at times, resort to judgement, further isolating victims who cannot stand up for themselves. She stressed the need for equal education, shared responsibilities in families, and the role of men in dismantling harmful norms.

Digital violence: not abstract, but lived

For many women in the room, the violence is not happening behind closed doors but through screens.

Local journalist Kekhriesenuo Kiewhuo recounted the constant barrage of misogynistic and sexualised comments she receives on her work, especially on platforms like YouTube and Instagram.

“It is not okay, and it is not fine with me,” she said, calling on all sectors, including the media, to speak up.

Actor, writer, and content creator Merenla Imsong spoke of how public women in Nagaland endure relentless online abuse, stating that, “When you become a public person, people think they have every right to judge you in every way possible,” she said. “I am not the dumping ground of unresolved emotions of frustrated people on the internet.”

She pointed out that internet bullying in Nagaland relies heavily on misogynistic language:

“Call a woman a wh***; call a man gay — it’s all rooted in our relationship to patriarchal expectations.”

Advisor to Naga Mothers’ Association, Dr. Rosemary Dzüvichu, added that online harassment—including explicit threats she recently received—shows why digital spaces must be treated as part of the gender-based violence landscape and why administrators of online platforms must also be held accountable.

On the other hand, she also noted that while digital violence is a genuine concern, it affects only a small section of Naga women. “Tell me—how many women in our rural areas are actually facing digital abuse? We have far more serious forms of gender-based violence within our homes and communities than what is being highlighted under digital violence,” she said.

A crisis hidden in plain sight

A shared theme across every speech was the severe underreporting and social tolerance of violence against women. Speakers highlighted persistent harmful practices such as polygamy, child marriage, dowry-like demands, and the lack of legal awareness in rural areas and stressed the need for stronger legal and institutional accountability, deeper collaboration between institutions, and more robust digital-safety structures.

They argued that economic empowerment for women, village-level awareness, and education must go hand in hand with dismantling patriarchal norms within families.

Several also called for the public release of anonymised data to reveal the true scale of the crisis, and urged society to treat domestic violence as a public concern rather than a private “family matter.”

In a message delivered on her behalf, Kaisa Rio emphasised that atrocities against women—whether physical, emotional, economic, or digital—“strike at the very core of human dignity.”

She reiterated that every woman deserves the right to safety and justice, and that these responsibilities lie with families, communities, institutions, and government alike.

The recent murder of Vihozhonu Zao, she reminded the gathering, is a sobering example of what happens when society waits too long to respond.

Yet the sharpest reminder came from grassroots worker Neingu Kulnu, who has spent years answering distress calls on the frontlines. She warned that violence is no longer a distant headline, nor something that happens only to “other families.”

Reflecting on how communities rally during public protests but rarely follow through once the placards are gone, Kulnu stressed that this is not about blaming anyone, but about recognising the reality unfolding within Naga society.

She said recent cases—including one this year where a mother murdered her own daughter in Kohima—force the question back onto every household: Are we truly safe? And if not, what responsibility does each community, tribe and family bear in confronting the crisis before it reaches their own doorstep?