Panel discussion in Dimapur highlights challenges of ethics, accountability, and transparency in digital journalism and reporting.

Published on Sep 13, 2025

Share

DIMAPUR — The rapid growth of digital technology and smartphone accessibility has blurred the lines between journalists and media practitioners, often raising critical questions about ethics, objectivity, and accountability in news reporting.

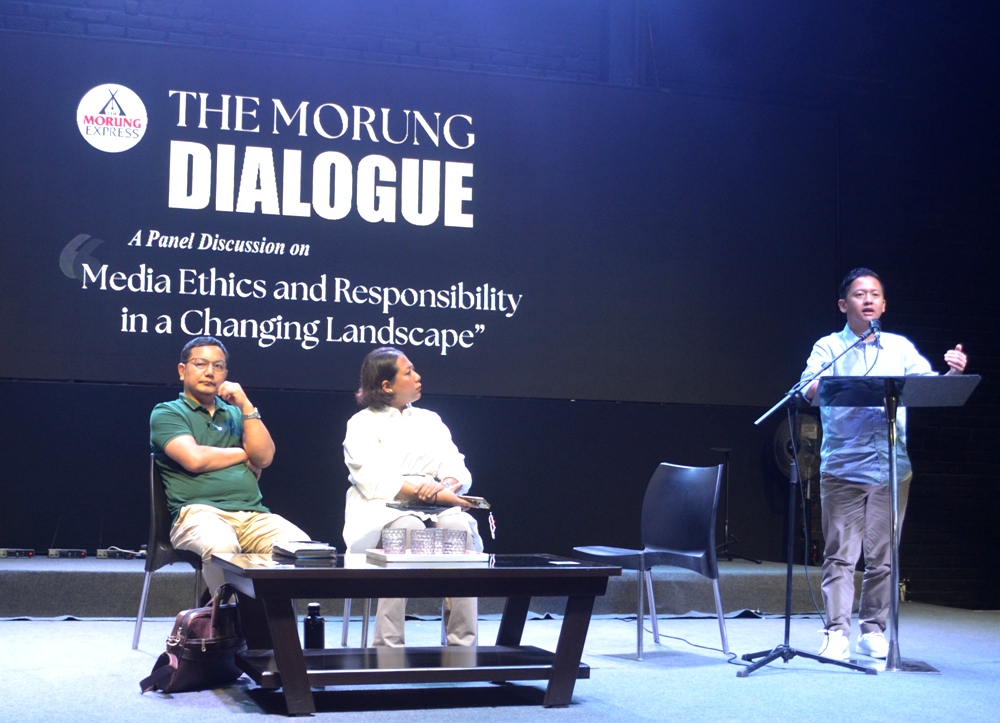

These concerns took centre stage at a panel discussion on ‘Media ethics and responsibility in a changing landscape’ organised by The Morung Express, in collaboration with the department of Information and Public Relations (DIPR), in Dimapur on Saturday.

The discussion featured Dr. Moalemba Jamir, associate editor of The Morung Express; Esther Verma, chief operating officer of Nagaland News Network; and R Lungleng, host of The Lungleng Show on YouTube.

Dr. Jamir noted that while digital platforms have democratised news creation, they have also amplified ethical concerns.

He underscored the distinction that while all journalists are media practitioners, not every media practitioner qualifies as a journalist. The danger, he said, lies in mistaking content creation for journalism, without adhering to values of fairness, neutrality, and accountability.

Also read: Nagaland: Illness anxiety drives patients online, raising mental health concerns

He warned against the growing influence of paid news, coverage-for-money, and sponsored content, which complicate the credibility of journalism.

Ethical fragmentation, he observed, is another challenge—partly due to varying standards across traditional press, digital media, and emerging platforms. For him, separating fact from opinion remained fundamental.

Transparency and responsibility

Jamir posed three guiding questions for media professionals: Who am I? Who are you? What am I doing? These, he argued, should drive constant reflection in the newsroom.

He lamented the lack of transparency in many media outlets, including well-established press houses, which often fail to disclose editorial objectives or identify key personnel. “If media demand transparency from institutions, they must embody it themselves,” he said.

On the second question, ‘Who are you?’, Jamir observed that journalists sometimes overstep boundaries, intruding into personal spaces or ambushing individuals on issues like Inner Line Permit (ILP) compliance.

Such practices, he said, are the responsibility of state agencies, not journalists. He urged the media to shift focus from scrutinising individuals to examining systemic accountability—such as how effectively regulations are implemented by the authorities.

The third question, ‘What am I doing?’, called for introspection into sensationalist tendencies. Jamir cautioned against framing issues in provocative binaries such as “outsider versus local,” which he said risks turning journalism into a participant in division rather than a neutral witness to facts.

Context as a pillar of truth

Adding to the discussion, R Lungleng underscored the role of context in ethical reporting. Without context, he suggested, perceptions of truth are easily misinterpreted.

In the digital age, where provocative content can generate quick views on platforms like YouTube, he warned against sensationalism that sacrifices substance.

He urged journalists to go beyond surface complaints and probe deeper into why situations occur.

Read more: Three hundred reasons for change: Nagaland’s PwDs struggle with token pension

‘The purpose of becoming an analytical reporter is to dig deep and find the truth,’ he remarked. Journalism, he added, should serve as a moral compass, free from the pressures of clickbait and propaganda.

For Lungleng, journalism must educate the public by placing issues in proper context, ensuring reporting is not only fair but also holistic in its interpretation of events.

Literacy and independence

Esther Verma highlighted the growing influence of real-time digital reporting, especially through YouTube channels and social media platforms.

While acknowledging their reach, she expressed concern that many private media houses lacked editors with strong backgrounds in media ethics. Without such leadership, she warned, unethical directions might be pursued.

Verification, she stressed, is non-negotiable. “Even small unverified pieces of information can trigger serious consequences. With powerful digital tools at everyone’s fingertips, the responsibility is immense,” Verma said. She added that reporters must remain vigilant not to incite hatred, violence, or chaos through their work.

Verma also called for greater media literacy—not only among journalists but also the general public. Collaboration between media houses, civil society organisations, and educators, she said, is necessary to help people identify misinformation and avoid falling prey to fake news.

At the same time, she questioned whether private media houses should ‘fall under DIPR’, warning that such a move could compromise the independence of the press.

She cited the recent Nagaland Legislative Assembly session where ‘selective media coverage’ raised doubts about criteria and regulatory oversight, stressing the need to clearly distinguish credible news channels from “mere YouTubers.”